Broadcasting: Nikesh Shukla

Award-winning author, screenwriter and comic book-obsessive Nikesh Shukla talks about the books, music and films that changed his life, his love of hip hop and finding solace in comedy.

It’s not often you get the chance to share a curry with someone whose way of thinking has truly shaped your own; someone whose words have both inspired and impacted yours. Well, I hate to brag (I don’t), but I have. On a sunny Tuesday afternoon, I was lucky enough to scoff a takeaway box full of The Tempeh Man’s finest curry on the corner of Leather Lane, with the brilliant Nikesh Shukla.

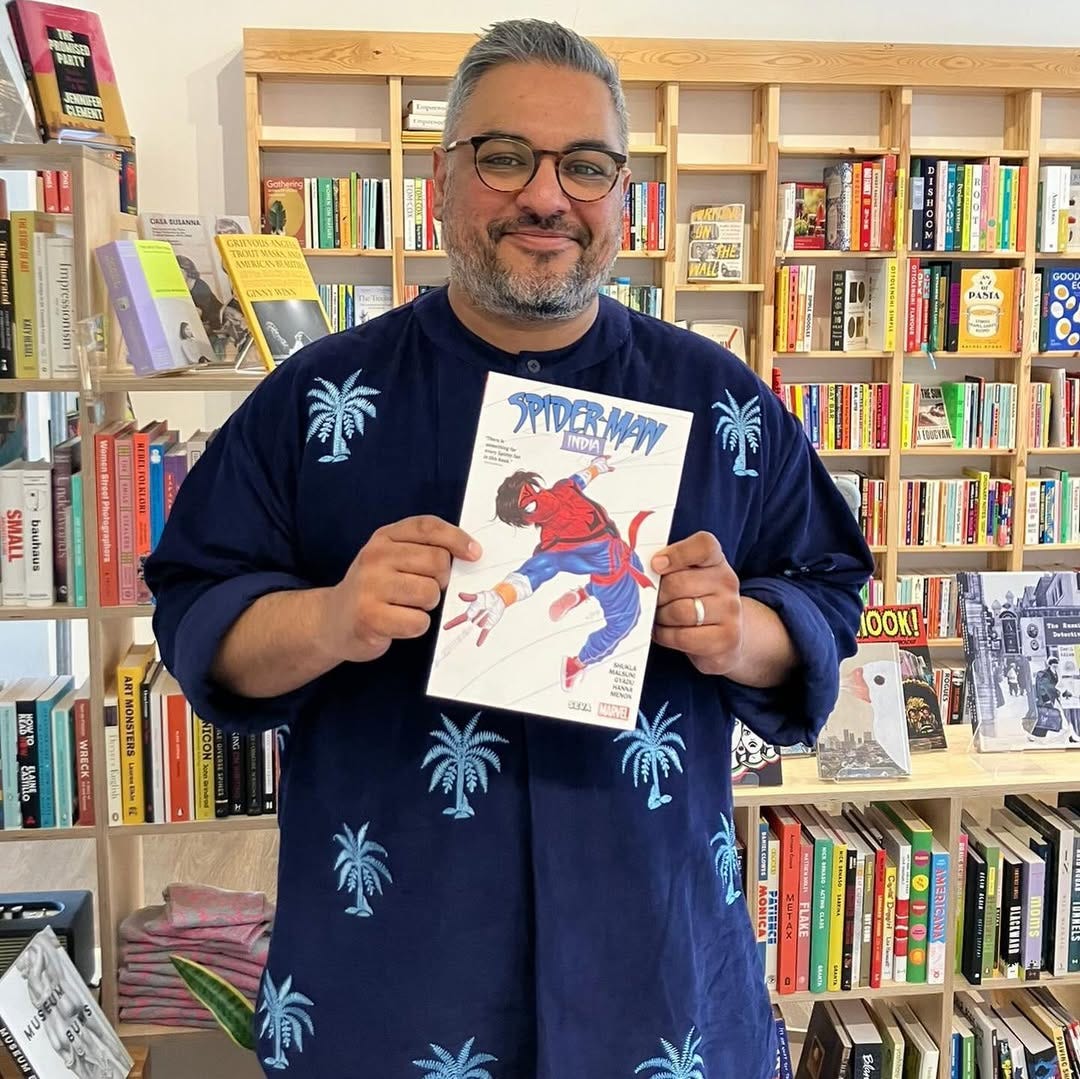

Co-founder of The Good Literary Agency and editor of best-selling essay collection The Good Immigrant, Nikesh was one of Time Magazine’s cultural leaders, Foreign Policy magazine's 100 Global Thinkers and The Bookseller's 100 most influential people in publishing in 2016 & 2017. Author of fiction and non-fiction, Nikesh also wrote the 2023 Spider-Man India miniseries Seva for Marvel, something he speaks about with the endearing enthusiasm of a teenager.

It’s the second time we’ve met, and I’ve sort of tried to tell him that I think he’s really cool, but I think he thinks I’m joking. He’s self-deprecating, but in a totally non-industry way. So many of the writers I meet go to such lengths to tell me just how little regard they have of themselves (which is equally as funny as it is depressing). Nikesh’s self-deprecation is much, much quieter. He’s softly spoken yet deeply impassioned, sharing stories of his desire to be a rapper, his love of sitcoms and why he’ll always pay it forward.

“I have seen peers who have never said a thing about race excel, because they have quietly gone about their work whilst I have loudly got on with activism. It isn’t even activism. It’s just asking for parity in the industry in which you work.”

It’s been about ten years since The Good Immigrant was published. In some respects, a lot has changed in terms of conversations around race and representation in that time. But it’s astonishing just how relevant the essays still are, despite that. What’s your perspective on that?

So much has changed in that time. We’ve seen what happens when people use “representation” in bad faith. I see it very much as a book of its time, so it’s both lovely and surprising that readers are still finding it today. I suppose the fact it’s had consistent sales over the ten years must mean that the essays still feel relevant! I’m very lucky to have worked with such talented contributors, including Reni Eddo-Lodge, Himesh Patel, Riz Ahmed, Vera Chok and Inua Ellams, who is now writing for Doctor Who.

I think it’s great that the book is finding new audiences, even if some of my thinking has moved on. That’s the case with anything I publish though; from the moment it’s released into the world, it’s no longer mine. It belongs to the readers. I continue to learn and evolve, and there are things that I look back on and feel ashamed of. It’s like when you re-watch a film as an adult that you used to love as a child, and you’re like - oooh, this hasn’t aged well! The film hasn’t changed, but you have. I remember first reading High Fidelity around the time that the John Cusack film came out in 2000. I re-read it much more recently to do a podcast about it and the experience was so weird because I had totally forgotten that the protagonist casually admits to sexual assault within the first ten pages. At the time, I totally skirted past it. Now I’m like, this is clearly an awful person. The book is exactly the same, but I’ve changed.

I think a part of that is growing up and maturing, but another part of it feels tied in with a wider cultural shift in what is deemed “acceptable”. There are things I used to watch or conversations I would have had that make me cringe when I think about them now!

I think about this a lot. Why were certain things or opinions once acceptable and are now not? I wonder whether our perception of what’s “acceptable” really has changed, or whether it’s just that there were fewer platforms for dissenting voices back then. Social media, for all its sins, has played a huge part in getting momentum behind those voices who are speaking up and advocating for what’s right. I think there’s always been an undercurrent of critical perspectives, but I don’t think people had access to them in the same way that we do now. Take James Baldwin and Toni Morrison - they were writing about racism and civil rights way before social media existed.

Talking about racism has burnt a lot of bridges for me, and there is a part of me that wishes I hadn’t published The Good Immigrant at all because it broke me. I have seen peers who have never said a thing about race excel, because they have quietly gone about their work whilst I have loudly got on with activism. It isn’t even activism. It’s just asking for parity in the industry in which you work. But I will continue to advocate for anyone who is marginalised through my writing because it feels like the only thing I can do. Growing up, I had so many opinions but I didn’t have a voice to voice them. I moved through my life thinking I was nothing, until I found writing.

Does writing make you feel less like “nothing” or does it just help you express those feelings of nothingness?

It means I can express those feelings. I’ve never felt good enough. I’ve never felt like the main character. That might sound simplistic but it’s what I am willing to share publicly. I’m just a neurotic writer at the end of the day! I’ve always felt like an outsider. I found myself in the Spider Man comics because nothing says immigrant kid from the suburbs with the weight of the world on his shoulders like Peter Parker. I gravitated towards comedy because it’s the home of the outsider. Growing up, my mum, my sister and I would watch every single American sitcom that was on: Saved By The Bell, The Fresh Prince of Bel Air…We had to watch them with the subtitles on because my dad would be listening to Hindi songs on full blast on the other side of the room. That’s actually still how I watch TV! My favourite sitcom is Frasier. It’s such a silly farce - the perfect encapsulation of high brow, low brow. The way a lie or a fallacy begets more lies and fallacies. It also represents such a pure time in my life. In the 80s, there used to be this guy who would drive around North West London in a Datsun with a car full of pirated Bollywood movies. We would rent them and watch the same film over and over again. There’s a generation of Bollywood films that I feel so close to because of that guy and I don’t even know who he is!

I want to touch upon what you said about comedy being the home of the outsider, because I think that’s the amazing thing about it; it can provide a safe space to exist for those who otherwise don’t feel able to. I was one of the only brown girls at my primary school and I used to lie and say I was Spanish because it felt more acceptable. For you, was feeling like an outsider related to your race and ethnicity?

Growing up, there was a self hating part of me that thought being brown wasn’t cool. That Bollywood films were something to make fun of. That sense of shame started to change for me when I saw the trailer for a BBC Two adaptation of The Buddha of Suburbia, starring a young Naveen Andrews shagging his way around London! It looked amazing, but I remember thinking I’d never be able to watch it with my parents because of how explicit the sex scenes were. But then the trailer said that it was based on a book by Hanif Kureishi. My TV viewing at home was very restricted but I had free reign in the library so I went and borrowed it. The first line of that book broke my brain apart. “My name is Karim Amir, and I am an Englishman born and bred, almost”. That “almost” changed my life. It goes on to be one of the funniest, most chaotic books I’ve ever read. It’s anarchic, punk and sexy. It made me feel like being an outsider was cool.

Your first novel, Coconut Unlimited, is about three hip hop-loving Asian boys in an all-white private school who start a band. Is it at all auto-biographical?

My cousin first introduced me to hip hop. He played me Don’t Believe the Hype by Public Enemy. Listening to that for the first time was a similar experience to reading The Buddha of Suburbia in that it unlocked something in my brain. I fell in love with hip hop after that, and it was in its golden era - Della Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, Wu-Tang Clan. I thought I wanted to be a rapper, but I was a very mediocre one, and what the world doesn’t need is another mediocre rapper! I just loved how hyper-regional and specific hip hop is. Chuck D refers to it as the Black CNN, and it’s that relationship between art and politics that I think is so powerful. I remember setting the video recorder to tape Do The Right Thing when it was on TV at midnight. That film has that same hyper-locality that I love in hip hop. The way everyone has their own storyline that culminates in this riot that is going to change the street forever is amazing. It really impacted my place in the world and what I wanted to write about.

At the time, I was lucky enough to be mentored by Deeder (Deedar Zaman), who was the lead vocalist for Asian Dub Foundation. He really helped me to find the political voice in my writing. I was writing a lot of short stories and poems, and I was published in an anthology called Tell Tales, edited by Rajeev Balasubramanyam, Courttia Newland and Nii Ayikwei Parkes, amongst others. They had such a huge impact on my life. I can’t pay them back, so I try to pay it forward. It feels like the least I can do. I had an awful time at school and I saw people be awful, but I am also very aware of the way class intersects with race, something rarely spoken about. My time in private education meant that I had access to the arts and literature and an incredible English teacher who is the reason I am here. I have experienced privilege and I think the least I can do is help people who haven’t, even if it’s a small drop in the ocean, so I do as much teaching and mentoring for free as I can.

I don’t think that is a small drop in the ocean though. It’s these small things that end up having a huge impact on people’s lives, and those same people go on to do the most incredible things that impact other people’s lives, and so on, don’t you think?

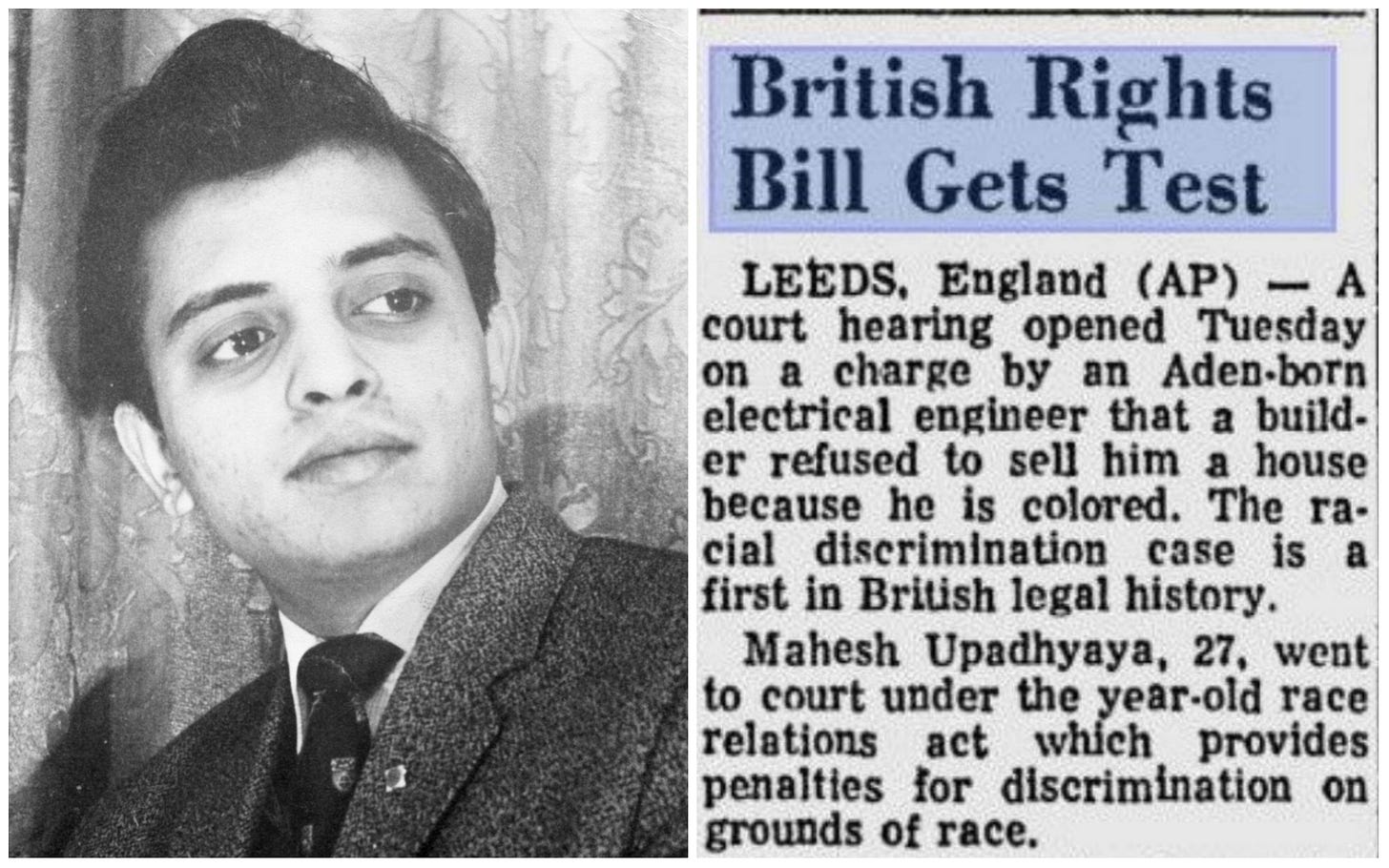

I’ve told this story before, but my uncle’s journey is a huge source of strength and inspiration for me. In 1968, he tried to buy a house in Huddersfield, but was told by the company that they had a “policy not to sell to coloured people”. The Race Relations Act had just come into play, and my uncle was the first person in the UK to bring a case of racial discrimination to court under the Act. He became a bit of a celebrity in the anti-racism movement. I didn’t know any of that until I was a teenager, but it really sticks with me. He was just a young guy trying to buy a house. His mother, my grandmother, came over to the UK from India and worked in a factory. She used to put a boiler suit over her saree, which is an image I really love. My grandfather worked in a Ben Sherman factory. My mum, who was born in Aden and then went to boarding school in India, came to the UK without being able to speak a word of English. And yet her brother, my uncle, made history when he tried to buy that house.

I read this thing the other day that has really stuck with me (OK, I watched it on an Instagram reel), but it was basically saying that it’s our parents’ first time living life too. Hearing about your family’s journey is a reminder to all of us to give our parents a bit of grace.

I think about this a lot. I used to feel so much pressure to be a return-on-investment kid and I’d resent my parents for making me feel like that. Until a dear friend told me something their therapist, a person of colour, said to them. They said - “when your parents told you that you’d have to work twice as hard to have the same opportunities as white people, they were 100% correct. You have to stop blaming them for that and start blaming institutional and structural racism instead”. It’s so true! Why do we blame our parents when they were just reacting to the world with the tools they had? You know that Philip Larkin poem that starts with, “they fuck you up, your mum and dad”, people forget that he goes on to say that it’s because they were fucked up themselves. It’s all cyclical.

My dad was born in Kenya and came over to the UK as a sixteen year old entirely by himself. He had to raise himself in a racist environment with The National Front at the end of his street. He nearly got bottled to death once. Of course he is going to parent me in the only way he knows how. My parents worked so hard to give me the life I have - why should I blame them for that?

We’ve spoken a lot about giving back, paying it forward, whatever you like to call it. Do you believe in the idea that we all have a purpose? If so, what do you think yours is?

To write Spider-Man 5?! I don’t know, I guess my purpose is to go to sleep at night feeling like I haven’t put badness into the world. That I’ve made the world the tiniest bit easier for my kids and other people’s kids. I think paying it forward IS my purpose. It’s hard to say anything meaningful. My desires feel banal. I want Palestine to be free. I want life to be easier for all marginalised people. I want trans people to feel like they can live their lives. I want a government that isn’t parroting the far right. I want our industry to stop being so performative when it comes to equality.

Follow Nikesh here!